Four Ways to Teach Across the Curriculum

When I was in school as a student, I would often question why we were learning material in only one subject. Why would I learn about a formula in algebra, an animal in biology, a performer in theater… and never hear about it again in any other class? As a student, this killed my curiosity at points… I would think things like “that actor is only important in theater, and has no other important contributions in the world.”

As a teacher now for seven years, I understand it. Teaching one subject is challenging enough – just choosing how you are going to teach the curriculum can be daunting. Should I use a lecture, a read-aloud, a Powerpoint? When I’m assessing students, should the assessment be graded based on completion, or on reading and commenting on answers? Is this something that can be assigned for homework, or would that confuse lower students even further? This does not even include factoring in time management, differentiation, and so much more.

There are many ways to get students engaged. One way is to “gamify” your classroom – this can be done by creating a Jeopardy board, or by running an escape room. Another way is to have students create textual connections between a movie, TV show, or other book they know. However, one method that I have found to be very effective, especially if the goal is to get students engaged in material and become interested in material, is to teach across the curriculum.

For example, take World War II (WWII). This was a devastating war, and it is clear to see that this belongs in a history class, or perhaps even a political science or geography class. But… what about other subjects?

There were, among other things, technological advancements that came from the war. Animals and plants had to quickly adapt if they wanted a chance at survival. Sculptors still sculpted, painters still painted, and actors still acted, yet I never learned about any of this in any technology, biology, art, or theater class.

Teaching WWII across the curriculum would have numerous benefits. For one, it would allow students to really understand the intricacies of the war. A theater teacher could discuss whether acting during that time was more challenging, due to the bleak nature of WWII, or if it was the light in an otherwise dark time. Biology teachers could discuss how plants and animals evolved in more detail.

It would also allow students to make a connection. That “a-ha” moment is one of the reasons I love teaching! There is no better feeling as an educator than finally watching your students finally understand something. By teaching across the curriculum, students would have a better opportunity to have that “a-ha” moment.

As an English teacher, it is very easy to fall into the trap of saying “I think the students should learn science, so here is one article about a plant.” While this is technically teaching across the curriculum – after all, you didn’t have to choose an article about a plant – there is so much more to teaching across the curriculum. Read on to find out a few more ways to be a cross-curricular educator.

Teaching With Your Colleagues

One way to be cross-curricular is to have students learn information across a theme. English and social studies courses would do this well, as would math and science courses. For example, reading a fiction text about a gay character in English course would match well with the social studies teacher informing students about Stonewall. Probability and Punnett squares would also appear to go hand-in-hand.

However, if you choose to teach across a theme, make sure that both teachers acknowledge this in the classrooms. In a certain New Jersey district, the English department gave their students an option of several books about the Holocaust. As students began reading these books, the social studies teacher did a two-week long unit about genocide, focusing on the Holocaust. It was in this way that students could see that the Holocaust was not only a social studies focus, but with a literacy focus, as well. The art teacher even became involved, and had students create a wall of butterflies, which symbolized hope from children, and that their souls would take on an immortal form.

Another way to be cross-curricular is to teach the same skill across different courses. Again, an English and social studies class seems to be a good matchup for this, as does a math and science class. However, there are other combinations that may work.

In a previous district I worked for, the science teacher would wear a purple shirt just about every day in school. About two weeks into class, he asked the students to make an inference about his favorite color. Without fail, each class said “purple.” When I taught these same students about inferences a few weeks later, I made sure to say, “You just made an inference, like how you knew that Dr. C’s favorite color was purple by noticing that he wore purple every day!” It was as though I could see the neurons of my seventh graders firing!

Another way to teach across the curriculum is to have teachers address the same themes of their respective subject areas in a project. Kelly (2019) provides an example of a “Model Legislature,” suggesting that across both history and English classes, students could write and debate bills before acting as a legislature deciding on if the bills move along the process.

One example of this from my career is when I was teaching Hatchet by Gary Paulsen to a group of sixth grade students. If you are unfamiliar with the book, Brian has to survive living in a forest when his helicopter crashes. Mentioned frequently in the book is the lake that Brian has to drink from. But… how big is the lake? Students in math class had to figure out how big the lake was by using formulae to determine the surface area, and had to write a few paragraphs explaining how they determined the answer. The math teacher graded the math section and put that in for his grade, and I graded the paragraph and put that in for my grade.

This is also a wonderful way to collaborate with your colleagues – and if things go well, you have a project for the following school year. Be aware, however, that this requires a lot of coordination and prep time with your colleagues This requires a lot of effort on the parts of all people involved, especially if you have different prep schedules. Also, many teachers may not want to spend extra time because of their own lives outside of school. Additionally, you may have to get the approval of administration.

If your colleagues do not feel like collaborating with you (or, for whatever reason, cannot), never fear! You still can teach across the curriculum yourself!

Teaching Without Your Colleagues

As mentioned earlier, it is possible to find an article about virtually any topic. There are many great resources, such as NewsELA, Actively Learn, Readworks, and countless others which have leveled articles about all different topics (Do be aware that many of these websites require you to sign up in order to receive their articles). Choosing a text from one of these websites is an easy way to add other curricula to your lessons – however, you must avoid being lazy. Try finding out what the students are learning from their other teachers. Even if the other teachers choose not to collaborate, you are still transferring student knowledge from one course to another.

Every year, in a lesson on context clues, I taught my students the poem “The Jabberwocky” by Lewis Carroll. This is a nonsense poem, designed to not make any sense; the poem begins “’Twas brillig, and the slithy toves / Did gyre and gimble in the wabe.” Here is how I made cross-curricular connections across various subjects.

Biology: When I first came up with the idea to teach this poem, I texted the science teacher and asked her if she had any plans on teaching about the predator-prey relationship. She had taught about this just the week before – perfect for me! I could ask the students if the Jabberwocky was more likely to be a predator or prey, as based on what the science teacher, Ms. L, taught last week! Students accurately described the creature as a predator, and properly cited evidence of “jaws that bite” and “claws that catch” as proof.

Theater: Whenever (one of many) nonsense words were read in the poem, I would ask a student what it means, and then have one brave student act accordingly. I even added a costume element – I always tell students that “brillig” is a weather word and then ask for what the weather is in the poem. Whatever weather is decided by the students has a designated costume; students have worn sunglasses, toted umbrellas, and donned scarves depending on the weather of the poem (During the pandemic while teaching virtually, I had to act out the poem while I wore a hoodie in my very warm classroom, which the students appeared to enjoy)!

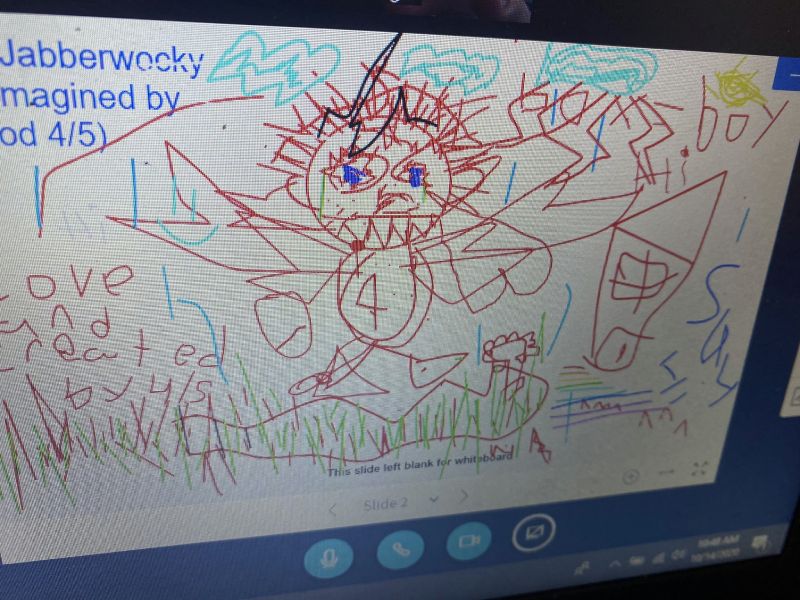

Art: When students (or I) was done acting out the poem, I had students draw a picture of the Jabberwocky, according to their imaginations. In non-pandemic times, students would spend time drawing, coloring, and shading the “vorpal” blade near the “tumtum” trees. During the pandemic, students worked together to draw on a paint-like platform what they imagined the Jabberwocky looked like.

Physics: In the poem, the unnamed narrator kills the Jabberwock with their “vorpal blade…” but, how much force did the narrator use? The formula for force is F=ma, where F equals force, m equals mass, and a equals acceleration. Take the mass of two volunteer students. Does the one with a larger mass need to have a higher or lower acceleration? For more advanced students, you can even provide them with values for acceleration, and have students calculate the amount of force needed to kill the Jabberwock.

There are, of course, many uses for this poem within an English Language Arts (ELA) context, beyond context clues. You can use this for grammar, asking students to determine the parts of speech of the various nonsense words. Capitalization could be taught – why are “Jubjub” and “Tumtum” capitalized, but not “bird” and “tree?” The teacher could also ask questions about figurative language –alliteration, onomatopoeia, and metaphors are all prominent in the poem. Finally, this could be used for rhyme scheme, as the poem has a common rhyme scheme (ABAB / CDCD, etc) seen in many other poems, as well as the occasional use of internal rhyme.

Teaching across the curriculum is very rewarding. Seeing a student finally have that “aha” moment is great to witness. Even if that moment is not experienced in your classroom, the ultimate goal of teaching is to get students to learn academic (among many other) skills. By teaching in an interdisciplinary way, you are helping students learn even more… and hopefully, engaging students in the process!

This article is available and can be accessed in Spanish here.

Kelly, M. (2019). Cross Curricular Connections in Instruction. Retrieved from https://www.thoughtco.com/cross-curricular-connections-7791.

Carroll, L. (1983). The Jabberwocky. Retrieved from https://www.poetryfoundation.org/poems/42916/jabberwocky.