Imaginative Education: Implementing the Mantra “Everything Is Wonderful” Into Practice

“Where do the clouds go?” A Kindergarten teacher puts mirrors on the ground and asks the students to observe the daily phenomenon of the mystery of water in clouds. “What is the secret life of water? What might it do when we are not looking?” The students’ sense of wonder is stimulated as they imagine themselves in the sky, pondering the puzzle of knowing there is water in the clouds, but not being able to see it. Students in these science lessons are engaging their imaginations through the stories to be found in the learning content which ties knowledge, memory, and understanding together. This is the heart of the educational theory Imaginative Education: looking for the story behind the study.

Imagination Magnification

When reflecting on what usually sticks with us after we leave school, it is stories and experiences that we connected with emotionally that remain. In 10th grade geometry, I learned about measuring right-angle triangles and “SOH CAH TOA” through a little boy who went to go ‘soak a toe’ in the river. Here my teacher used humor and story to help me learn trigonometry by finding an emotional core in the topic, which I still remember from mathematics that year and to this day.

My teacher used the fundamentals of the educational approach Imaginative Education (IE), which focuses on tapping into students’ imagination to make learning more meaningful.

Imaginative Education uses “cognitive tools” as learning tools to guide teachers in creating units, lessons, and activities that develop students’ imaginations. Educators are already using cognitive tools when they find the “story” in the topic and then bring that story to life for students.

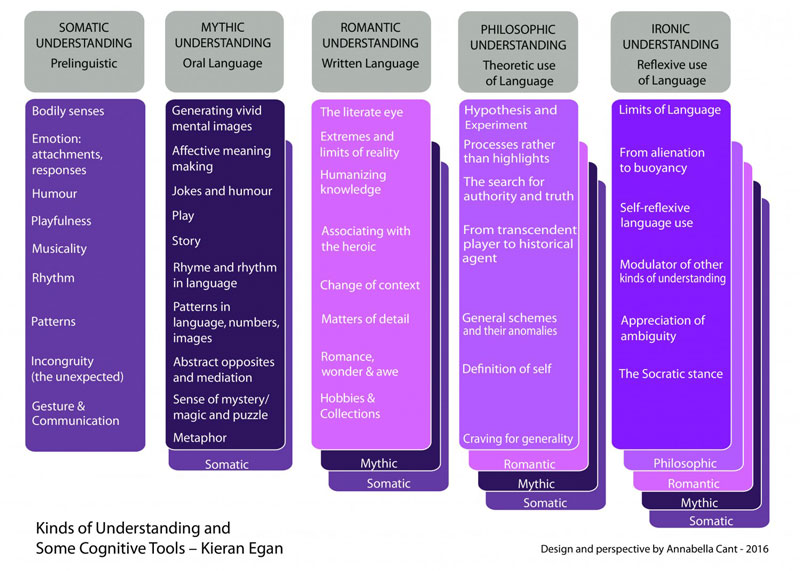

As seen in the diagram below, we can spark imagination in students through the cyclical structure of the cognitive tools. They reflect the development in learners; we first learn somatically, through the knowledge that our bodies give us, and then move on to a storied understanding – mythic understanding – where we use mythic cognitive tools to discover the world around us. We can work with students as they use the types of understanding in their educational development, similar to layers that keep getting added in a concept or topic when Imaginative Education is used.

Imaginative Education Beginnings

Imaginative Education (IE) was created by Dr. Kieran Egan and developed by CIRCE (the Centre for Imagination in Research, Culture, & Education) at Simon Fraser University in Vancouver, Canada. Dr. Gillian Judson, in her role as the Executive Director of CIRCE, continues to expand and develop the approach though Master’s programs, professional development courses, publications, and more.

One of my university lecturers participated in a professional development course in IE and shared her learning with us students studying the International Teacher Education for primary schools (ITEps) program at NHL Stenden University in the Netherlands. We participated in a workshop on the theory and practice of IE and the ways in which we could use the cognitive tools to plan units and activities.

When I was introduced to Imaginative Education, the philosophy resonated with me. I realized that it connected to a reason why I decided to become a teacher in the first place: expanding a child’s imagination to help them learn about the world through how they experience it to be true.

I never knew that there was a field of study supporting the imagination in education, and my interest and motivation to learn more led me to interview both Dr. Judson and Dr. Egan to gain a better understanding of Imaginative Education and cognitive tools. To further explain how the cognitive tools work, I am going to focus on two of them, the tools that align with Mythic and Romantic ways of understanding, as they are the most important ones for primary school teachers.

What are Cognitive Tools?

Cognitive tools are the way that we make sense of the world and stem from the different ways in which we understand it. Mythic understanding incorporates cognitive tools like story, visual imagery, myths, and mystery. Mythic cognitive tools are valuable for all educators but more important for early primary teachers as students’ worlds are grounded in Mythic understanding in their formative years. Lindsay Zebrowski, an early primary teacher who has completed her Master’s degree in IE, uses the cognitive tools in the unit “Media Detectives”, created by Dr. Kym Stewart. Students become detectives to uncover how they are targeted by media and advertising. She uses Metaphor, Binary Opposites, and Joking and Humor – and especially Roleplay (an aspect of Games and Drama) – as her students take on their special assignments as media detectives.

As students come to depend more on reading to make sense of the world, teachers can use a new set of cognitive tools that relate to this method of understanding: the romantic cognitive tools. This doesn’t mean that students only learn through reading and writing, but that students are now more able to make meaning with the tools that literacy brings. Since students’ world is “romantic” (e.g. they are drawn to Extremes and Limits of reality, weird and wonderful things, Heroes and amazing humans, for example), they get more excited about learning when teachers develop imaginative units that use the romantic cognitive tools. Romantic cognitive tools are particularly relevant for students in grades three to seven, compared to the later years of middle school and high school when they begin to develop more philosophical understandings of the world.

But How Do I Use the Cognitive Tools?

In our Imaginative Education workshop, a group of Year 2 students designed a Grade 5 drama unit, where students could learn about theatre through the cognitive tools of Collections and Sets, Heroic Qualities, and Extremes and Limits. As part of the unit, students categorize different dramatic archetypes into groups, create a list of possible heroic qualities for each character, and explore the extremes and limited forms of different types of theatre including black box theatre, outdoor theatre, and melodramatic acting (Babin, Cienski, & Reinders, 2019).

After our course on IE, we students found that it was a clear, uncomplicated transition to develop uses for the cognitive tools in lessons, hooks for lessons, unit planners, and end assessment. Cognitive tools are easily employed in unit and lesson planning because as teachers, we already encourage students to see the wonder in the world. Imaginative Education recognizes what is fundamentally interesting about a topic by focusing on the core story behind it.

In the interview with Dr. Egan, he mentions how this is what is meant by imaginative engagement: a focus on what schools may be neglecting. According to him, the tools are just hints of how to bring to life whatever it is you are teaching. The cognitive tools are all trying to do the same thing: mixing color into potentially dull matter.

Imagination is not Automatically Education

The cognitive tools, bringing together imagination, physical brain development, and knowledge, have allowed students from all over the world to thrive. Yet, in the words of Dr. Judson, not everything is a cognitive tool; a cognitive tool connects knowledge (curriculum content), our cognition, with emotion. This is what makes students understand and retain knowledge.

One of the biggest misconceptions about IE is that it can’t be used to cultivate academic success. School communities may be skeptical of IE’s academic value because imagination makes people think about play and not work or learning. Rest assured: students using the IE approach learn a lot about the world and earn better grades. This is due to the internalization of learning brought upon by using the effective cognitive tools, which help students remember as they tie emotion with knowledge and engage their imagination with learning (TEDx Talks, 2017).

In her article “The Role of Mental Imagery in Imaginative and Ecological Teaching”, Dr. Judson argues that the advantage of using cognitive tools with curricula is that it creates diverse connections between subjects and makes the curricula more accessible for the students. “By imaginatively grasping knowledge, children make it, reciprocally, become a part of them” (Egan, 1997, p. 62, as cited in Judson, 2014).

Connection to Inquiry-Based Learning

The tools are accessible to teachers and students if the curriculum is flexible in the delivery of the lesson, employs inquiry-based learning and promotes wonder and discovery; the International Baccalaureate’s Primary Years Program, the International Primary Curriculum, or the Common Core already incorporate these ideas.

Speaking from personal experience, the cognitive tools are not as abstract and difficult to integrate as they may seem to some. I was educated through the Primary Years Program, where I had learning experiences similar to using the cognitive tools. For example, in fifth grade, we discovered how to be an advocate for change in the world through the romantic cognitive tools: extremes and limits, (how can humans create change in situations of crisis), and revolt and idealism (how challenges to the norm can generate change).

The next step is to begin the discussion of the success of the cognitive tools with educators around the world– most of whom we are already speaking a common language with by focusing on developing effective forms of education. It is Dr. Judson’s hope that educators look at their curriculum through different lenses, to identify how IE can be a better approach for teaching and learning.

Imagination Ambassadors and Schools

For Dr. Judson, the utility of practicing IE is what makes us ambassadors, champions, and accomplices. When inquiring into which schools have adopted the Imaginative Education philosophy, the answer is clear: the teachers are the instruments of change. It is Dr. Judson’s vision to create an “imaginative schools network” in the future, where schools with different curricula, the British Columbian curriculum, Common Core, and Montessori schools, will be connected with the IE philosophy.

Dr. Egan states how everyone who is passionate about the imagination is and can be an ambassador for IE. Currently, the state of affairs is that IE schools are “islands of change” around the world, but as the philosophy is relatively “new,” more information about IE and their workshops, courses and Master’s programs can be achieved through the CIRCE website: http://www.circesfu.ca/. Additionally, the ImaineED website gives tips for new Imaginative Educators: http://www.educationthatinspires.ca/tips-for-imaginative-educators/.

The Significance in Story

Dr. Egan’s theory recognizes a diverse but powerful aspect of humanity– our capacity for imagination. The imagination is the driving force of our development, and when stories and cognitive tools trigger emotion in imagination, we connect with the content and learning becomes meaningful. According to Dr. Judson, “What has previously been thought of as a distraction for learning is now a requirement for learning” (TEDx Talks, 2017).

However, the biggest impact of Imaginative Education is when those who learn about it recognize that it aligns with what they already value, and they write and share about it. Perhaps what connects us is our keen interest in knowing about other humans’ world experiences, why SchoolRubric’s philosophy is “What’s Your School Story?” and why Imaginative Education is the tool for students to build themselves from the stories they learn.

This article is available and can be accessed in Spanish here.

Babin, C., Cienski, T., & Reinders, J. (2019). Drama Unit Plan for Plotting Imaginative Tools. Unpublished manuscript.

Dartenne, L. (2019). Water Cycle Unit Plan for Plotting Imaginative Tools. Unpublished manuscript.

Egan, K. (1997). The Educated Mind: How Cognitive Tools Shape Our Understanding. Chicago: University of Chicago Press.

IERG. (2015). A brief guide to Imaginative Education. Retrieved on November 28, 2019, from http://ierg.ca/about-us/a-brief-guide-to-imaginative-education

Judson, G. (2014). The role of mental imagery in imaginative and ecological teaching. Canadian Journal of Education, 37(4), p. 1-7.

TEDx Talks. (2017, October 30). Engage Emotion, Engage Imagination: Cognitive Tools At Work [Video file]. Retrieved on November 26, 2019, from https://youtu.be/loIZyzPVgrU