What Makes Adolescent Reading Different?

Student performance on literacy assessments, especially in reading, significantly decreases in grades 4 and 5. What happens in these intermediate grades?

As Chall’s (2000) research documents suggest, there is a critical transition point at which students begin reading to learn as opposed to learning to read. This transition typically happens around 4th or 5th grade, and it is what makes adolescent literacy different.

Most subject/discipline specific teachers of 4th–12th graders can cite many examples of instances in which their students were able to decode text but were unable to comprehend it. The simple decoding of words and recalling basic information of a text are characteristic of the learning to read phase. Yet, as students progress through school, they are exposed to more complex ideas and more detailed information through discipline-specific texts. Exposure to these texts, as well as related digital media, is essential so that students not only learn content, but also learn to analyze information and develop new ideas and understandings. Students are expected to read texts to learn about the disciplines. Adolescent students do this at varying degrees as they march through a regimented schedule, jumping from one discipline to the next. This results in the greatest challenge: how do we ensure that students are developing literacy skills in all subjects/disciplines to ensure their academic success in a variety of situations?

Going beyond the textbook is a good way to provide students with a wide variety of content and discipline-specific texts while promoting background knowledge and vocabulary development. However, it is important to note, that there is debate among reading experts as to whether this is the best way to accomplish this goal. According to Shanahan (Wexler, 2018), there is no evidence that providing differentiated reading improves student reading. He explains that students benefit more from reading texts that are harder and at respective grade levels. In light of this assertion, I ask that you consider the work of another key reading researcher, Allington. In Every Child, Every Day, Allington and his co- author, Gabriel (2012) explain that each student must read texts he or she understands. They explain, understanding what you’ve read is the goal of reading. But too often, struggling readers receive interventions that focus on basic skills in isolation, rather than on reading connected text for meaning. This common misuse of intervention time often arises from a grave misinterpretation of what we know about reading development (Allington and Gabriel, 2012)

It makes sense that adolescent readers should be given plenty of opportunity to practice with texts that they can read accurately, fluently, and with understanding. In addition to providing exposure to background knowledge and seeing vocabulary words in context, accessible texts give readers an opportunity to build reading “muscle memory.” Fluency necessitates practice. It can be thought of as the bridge from decoding to comprehension. As teachers, developing content knowledge and reading fluency is essential. (McKnight and Allen, 2018).

Now the question is, “How do we do this in our classrooms?” As experts in our various disciplines, how do we provide students with the kind of practice and collaborative experiences that will yield growth in literacy skill development, while teaching our content?

Creating targeted, focused, and chunked instruction paired with deep disciplinary study that requires the use of advanced literacy skills yields significant results. Here’s how it can work:

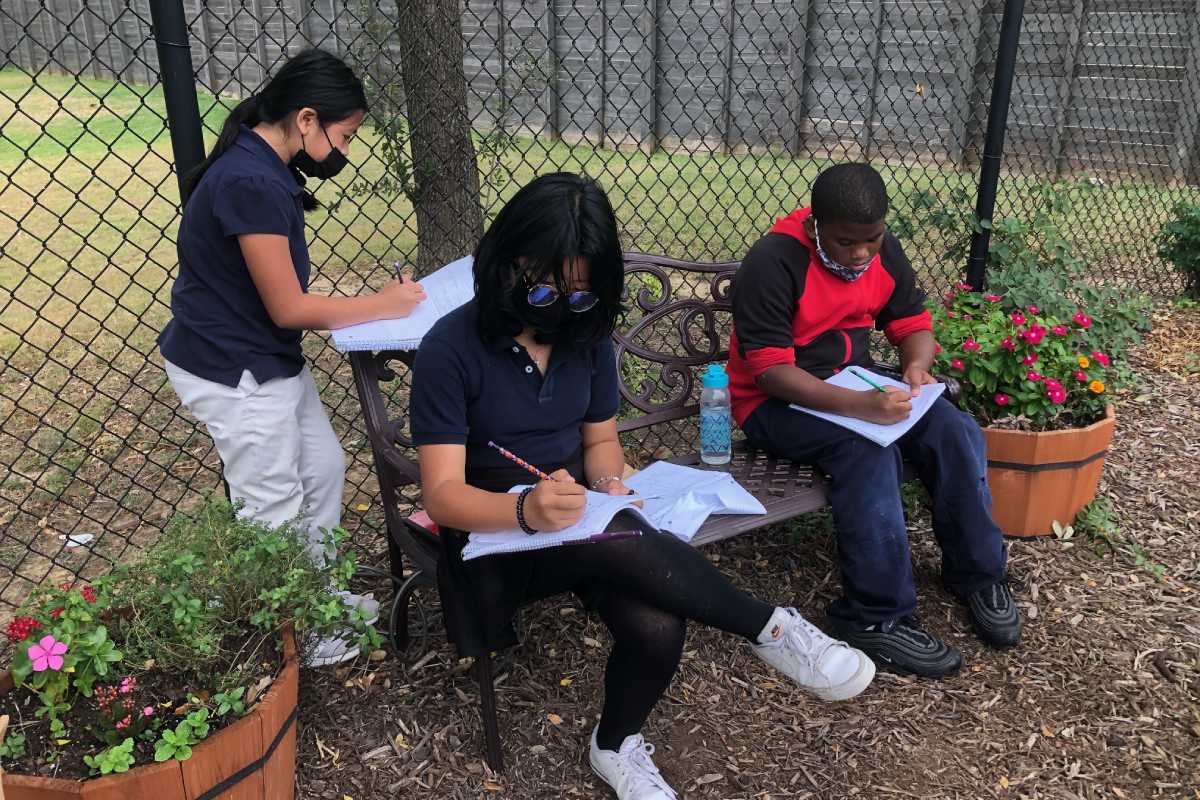

The teacher presents a short mini-lesson that focuses on a single instructional “chunk” of information, content, or literacy skill. Often this is followed by a brief activity in which the whole class reviews concepts and practices skills that were taught during the mini-lesson. Then small teams of students rotate through stations. At each station they are presented with a short, specific activity that:

1. gives them an opportunity to practice, review, and/or apply the skill or content that was taught during the mini-lesson,

2. they complete with some level of cooperation, and

3. offers them some small choice in how they proceed with the activity.

This structure allows for direct instruction of content and discipline-based literacy skills and provides opportunities to differentiate instruction. When instruction within the content areas is developed using this model, skills are not taught in isolation and students receive ample practice time. This is how we develop adolescent literacy skills and raise student performance.

Allington, R., & Gabriel, R. (2012). Every child, every day. Educational Leadership, 69(6), 10- 15.

Chall, J. S. (2000). The academic achievement challenge: What really works in the classroom? New York: Guilford Press.Jensen, E. and Nickelsen, L. (2008). Deeper learning: 7 powerful strategies for in-depth and longer-lasting learning. Thousand Oaks, CA: Corwin Press.

McKnight, K. S. and Allen, L. H. (2018). Strategies to support struggling adolescent readers, grades 6-12. Lanham, MD: Rowman & Littlefield Publishers.

Wexler, N. (2018, April 13). Why America Students Haven’t Gotten Better at Reading in 20 Years. Retrieved from The Atlantic: https://www.theatlantic.com/education/archive/2018/04/-american-students-reading/557915/